Curated by: Dr. Shane Turner

17 MAR 2025

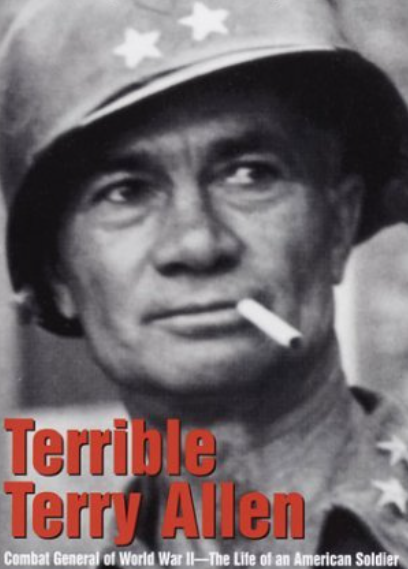

The Unfiltered Story of Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen, as Told by a Salty Old Vet

Audio File Discussion: Terrible Terry Allen – A Badass General’s Unfiltered Story

Listen up, you sorry bastards. I’m about to lay down the goddamn law about a man you should’ve been taught about in basic training but weren’t because the history books are written by rear-echelon motherfuckers with clean boots and soft hands. This is the story of Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen “Terrible Terry” to those who knew him, and he was the most genuine, no-bullshit general officer to ever wear stars in the United States Army.

“Terry Allen was one of my favorite people. He was colorful as hell, and he didn’t give a damn for hell or high water.” — Ernie Pyle, War Correspondent

If you’re some cherry who’s never heard of this magnificent bastard, strap in tight and grab a drink. This ain’t gonna be some starched-collar history lesson. This is raw, unfiltered truth from someone who respects what real leadership looks like. By the time I’m done, you’ll understand why enlisted men loved him, why officers either worshipped or hated him, and why he’s the kind of leader every one of us grunts would follow into the gates of hell carrying nothing but a pocket knife and a bad attitude.

BORN TO RAISE HELL

Terry Allen didn’t just join the Army, he was practically born into it, kicking and screaming on April 1, 1888, at Fort Douglas, Utah Territory. No April Fool’s joke here; this kid was forged for combat from day one. His old man, Colonel Samuel Allen, put in 43 years in the Army, and his grandfather on his mother’s side was Colonel Carlos Alvarez de la Mesa, a Spanish officer who fought for the Union at Gettysburg. Military wasn’t just a career in the Allen house—it was the blood in their veins, the air they breathed.

Growing up on cavalry posts across the American frontier, little Terry was surrounded by the real deal, hard-bitten horse soldiers who didn’t give two shits about polished brass or parade-ground bullshit. By age 10, this kid could ride like a Comanche, shoot straighter than most troopers, chew tobacco, gamble with enlisted men, and swear like he was born doing it. The military wasn’t something Terry aspired to, it was what he was, down to his bones.

But here’s where it gets interesting: Terry had a stutter so bad it would’ve sidelined most men. When he talked, words caught in his throat like they were fighting to get out. The other officers’ kids mocked him mercilessly. Did Terry give a fuck? Not one. He just kept pushing, kept fighting, kept moving forward like the unstoppable force he’d become.

“He was raised to be a soldier. It wasn’t a job—it was his goddamn birthright.” — Army veteran who served under Allen

At 19, Terry swaggered into West Point in 1907, figuring he’d make it official. Problem was, the academy’s aristocratic horseshit didn’t sit well with a kid raised by enlisted men in the dust of frontier posts. He racked up demerits like they were going out of style dirty uniforms, smuggled hooch, missing formations, even cheating on exams. The silver-spoon cadets, with their perfect accents and family connections, sneered at his stutter and rough manners.

Terry gave them the middle finger in his own way: he found his place on the polo field. As team captain, he showcased the leadership that would define him. The standard polo goal was eight yards wide, but Terry made his men practice shooting through a target one yard wide, one-eighth regulation size. Why? Because he fucking could, and because it was a giant “fuck you” to everyone who thought he wasn’t good enough.

When they faced a regional champion team expected to wipe the floor with them, the results spoke volumes. The champions took 40 shots at goal and made only seven. Terry’s squad? Eight shots, eight goals. Complete domination. That’s leadership taking a bunch of misfits and turning them into precision killers.

Despite his polo prowess, West Point still couldn’t handle him. Terry flunked math and ordnance courses, getting the boot after three years. Did that stop our boy? Hell no. He dusted himself off, enrolled at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and clawed his way to a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1912. Then, through sheer balls and determination, he secured a commission as a second lieutenant in the cavalry, effective March 3, 1913.

His first real taste of action came patrolling the U.S.-Mexico border, chasing Pancho Villa’s bandits through the desert. Harsh conditions, sporadic firefights, and constant danger Terry loved every minute of it. This wasn’t some fancy parade-ground duty; this was real soldiering, and Terry took to it like a duck to water.

WORLD WAR I: THE MAKING OF A LEGEND

When the Great War kicked off in Europe, Terry was chomping at the bit to get in the fight. But the Army had different plans, sticking him in a supply unit stateside, shuffling paperwork and counting beans. That shit wasn’t gonna cut it for a man like Terry.

In 1918, he pulled a move so ballsy it would make a drill sergeant blush. He crashed an infantry officer graduation ceremony, strolled up to the commandant who was handing out certificates, and when asked who he was, looked the man dead in the eye and said, “I’m Allen.” The commandant, not wanting to look like an idiot, assumed Terry had been part of the course and signed him off. Just like that, Terry was a temporary major in the infantry, headed to France with command of the 3rd Battalion, 358th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division.

“I wish the war hadn’t stopped when it did. It’s a damn shame. I was just beginning to get good ideas about commanding infantry battalions. I wish I could go back to the front and try them out.” — Terry Allen after the Armistice

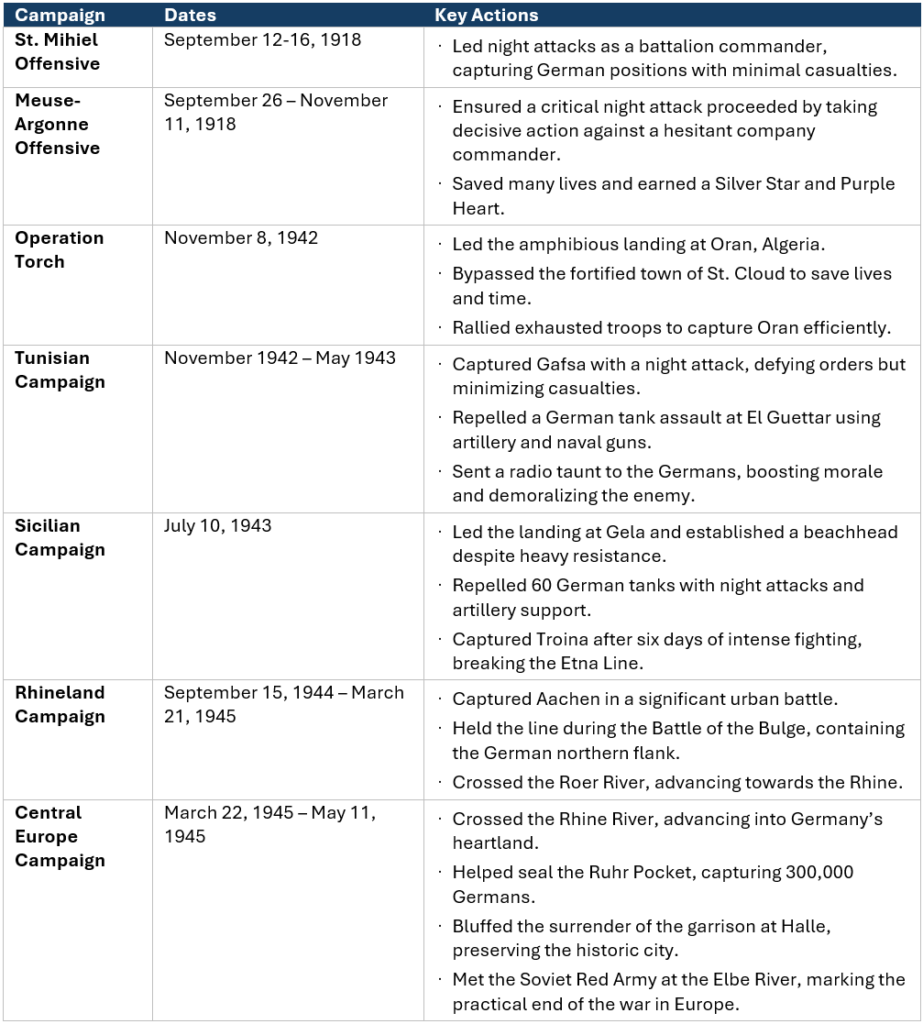

The blood-soaked trenches of the Western Front were where “Terrible Terry” truly came into his own. At St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne, the biggest, bloodiest battles America had ever fought, he revolutionized infantry tactics with night attacks. Sneaky, brutal, and damn effective, they caught the Germans with their pants down while minimizing casualties among his own men. Terry wrote home about the carnage, companies reduced to 40% strength, but believed night fighting saved lives, and he was right.

His men would follow him through the gates of hell because they knew he’d be right there with them, not sitting in some chateau miles from the front. He ate the same garbage food, slept in the same mud, and faced the same bullets. They didn’t call him “sir” or “general”,they called him “Terry,” and he loved it.

Terry took lead like it was his job, wounded four separate times. But the wildest injury? A bullet to the face that, instead of killing him, somehow fixed his goddamn stutter. I shit you not. Some Kraut’s bullet smashed through his jaw, and instead of dying like a normal human being, Terry walked away talking clearer than a radio announcer. Did he milk his wounds for a trip home? Fuck no. After the first one, he woke up in an aid station, looked around confused, saw the medical tag hanging from his uniform listing his injuries, ripped that bitch off, and walked right back to the front line.

Terry wasn’t just a hard-charging maniac, though. He had leadership instincts that couldn’t be taught in any academy. One night before an assault, a company commander froze up—panic in his eyes, refusing to advance into what he saw as certain death. Terry didn’t waste time with a pep talk. He pulled his sidearm, shot the guy in the ass, and growled, “There, you’re wounded. Get the hell out.” The exec took over, the attack proceeded on schedule, and they took the objective with 20 casualties instead of the 200-300 the brass had predicted. Harsh? You bet your ass. But in war, hesitation kills, and Terry knew it.

For his gallantry in action near Aincreville, France, on October 24, 1918, Terry earned a Silver Star. He also picked up a Purple Heart for the scars he collected. When the Armistice hit in November, he stayed in Europe with the occupation force until 1920, even playing polo against the Brits and becoming drinking buddies with Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII)—though Terry had no idea who he was throwing back beers with until much later.

BETWEEN THE WARS: THE MAVERICK CAVALRYMAN

After the war, Terry’s temporary major rank evaporated, and he dropped back down to captain, standard peacetime bullshit that would’ve crushed a lesser man’s spirit. Didn’t even faze Terry. His reputation was growing, and he knew his time would come again.

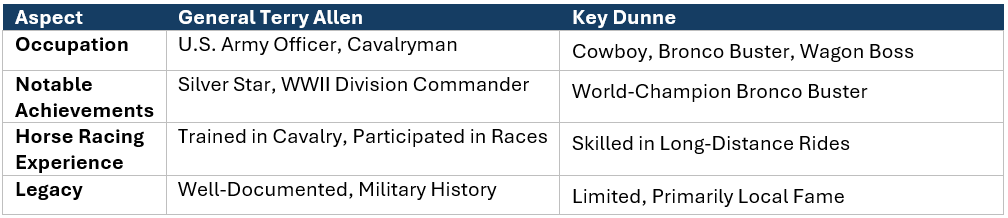

In 1922, the Army tapped him for a publicity stunt that would make headlines across the country: a 300-mile horse race across Texas against cowboy legend Key Dunne. The cattle barons and rodeo promoters wanted to prove their rough-and-tumble wranglers could outride the military’s best. They didn’t count on facing Terry Allen.

From day one, Terry dominated, covering 50 miles while Dunne struggled to 30. By day three, he was so far ahead he actually stopped at a diner for breakfast. The waiter, not recognizing him, started running his mouth about the race: “That Army guy is probably good, but he doesn’t stand a chance against a real cowboy.” Terry just grinned and replied, “Name’s Terry Allen. I’m the Army guy, and last I checked, I’m kicking his ass.” The restaurant comped his meal.

Later that day, word came that Dunne’s horse was struggling, no feed in sight. Terry could’ve coasted to an easy victory, but that wasn’t his style. He sent an Army car with feed and water to keep Dunne in the race, then beat him by seven hours anyway. Honor and balls, that was Terry Allen in a nutshell.

“Get this—the sumbitch sent his opponent food for his horse, then beat him by seven hours anyway. That wasn’t just winning; that was proving a goddamn point with class.”

The interwar years saw Terry grinding through the Army system. He served at Camp Travis and Fort McIntosh in Texas, then with the 61st Cavalry Division in New York City. He hit the books at the U.S. Army Cavalry School at Fort Riley, Kansas, and the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, where he graduated 221st out of 241 students, with Dwight D. Eisenhower taking first place.

The rankings didn’t matter to Terry. He knew what made a real leader, and it wasn’t test scores. During this period, he rewrote cavalry doctrine, publishing “Reconnaissance by Horse Cavalry Regiments and Smaller Units” in 1939, a manual that became the gold standard. Tanks were emerging as the future of warfare, but Terry still saw a vital role for horses as mobile scouts. He was ahead of his time, even if the brass didn’t get it.

Life wasn’t all military for Terry, though. In 1928, he married Mary Frances “Pinky” Robinson, a fiery El Paso gal who matched his independent spirit. Their son, Terry Allen Jr., arrived in 1929, giving the hard-charging officer another dimension to his life. Between assignments, he hunted, drank, played poker, and built a family life that grounded his warrior spirit.

By 1940, as war clouds gathered over Europe again, Terry had risen to brigadier general. When Pearl Harbor dragged America into World War II, he was ready for the next chapter of his remarkable career, one that would cement his legacy as one of the greatest combat leaders in American history.

WORLD WAR II: THE BIG RED ONE UNLEASHED

By May 1942, Terry was a major general with two stars on his shoulders, handed command of the 1st Infantry Division, “The Big Red One.” This wasn’t some parade-ground outfit; it was America’s first division, a storied unit with a proud history. Terry, teamed up with assistant division commander Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt Jr. (son of the former president and a badass in his own right), was about to turn it into something even greater: a killing machine that struck fear into the hearts of the Wehrmacht.

Terry’s leadership philosophy remained unchanged from his trench days: take care of your men, focus on what matters, and fuck the rest. Salutes? Uniforms? Morning reports? Chickenshit details could pound sand. He let his men call him “Terry,” drank with them, gambled with them, and treated them like the professionals they were. His only non-negotiable rule: keep your rifle clean and functional, because that’s what keeps you alive in combat.

“Terry Allen never asked a soldier to do what he himself would not do. And there was damn little Terry Allen wouldn’t do.” — 1st Division veteran

North Africa: Operation Torch

On November 8, 1942, the 1st Infantry Division hit the beaches of Oran, Algeria, as part of Operation Torch, America’s first major amphibious assault against German-held territory. They landed at midnight, catching the Vichy French defenders with their pants down. The objective: seize the city and its vital airfield, 25 miles inland.

The landing went textbook-smooth, but then they hit St. Cloud, a fortified town bristling with guns. Most commanders would’ve either flattened it with artillery (killing civilians) or launched a frontal assault (killing their own men). Terry saw a third option: he had one battalion surround the place to contain the enemy, then bypassed it completely with the rest of his division. St. Cloud had no strategic value, it was just a speed bump on the road to Oran. Why waste American lives taking it?

The march to Oran was brutal, 25 miles through unfamiliar terrain, carrying full combat loads after a wet landing. By the morning of November 10, his boys were dead on their feet, taking shelter in a roadside ditch from sporadic artillery fire. Terry walked the line, saw their exhaustion, then stood up, pointed to Oran in the distance, and bellowed: “There’s a lot of good-looking girls in that city, ready to welcome the liberating Americans. Where the fuck are you going?” The men laughed, got up, and pushed on to take the city by dawn. That’s how you motivate tired troops, not with threats or bullshit speeches, but with humor and common sense.

After securing Oran, higher headquarters wanted to carve up the 1st ID, parceling its units out as support for other operations. Terry wasn’t having any of that shit. He stormed into General Eisenhower’s headquarters, looked him in the eye, and demanded: “Is this a private war, or can anybody get in?” Ike, impressed by Terry’s chutzpah and recognizing his division’s capabilities, reversed course and kept the Big Red One intact as a fighting unit.

The Tunisian Campaign: Night Fighting and Psychological Warfare

In March 1943, orders came to take Gafsa, Tunisia, a strategic town about 45 miles from Oran. The plan called for an attack at dawn on March 17th. Terry thought that was stupid, attacking when the enemy could see you coming? Fuck that noise. He ordered his division to attack during the night of the 16th instead. By the time the sun rose, the 1st ID had rolled over Gafsa with minimal casualties and secured all objectives.

General George Patton showed up at first light, expecting to see a battle in progress. Instead, he found Terry sipping coffee in a captured building. “What the hell’s going on? Why don’t I see any movement?” Patton demanded. “Battle’s over, George,” Terry replied coolly. “I already have all the objectives.” Patton was furious—not that Terry had failed, but that he’d succeeded in a way Patton hadn’t envisioned.

“Why would I beat my brains out for a yard and a half when I could just pass the ball for 40 yards?” — Terry Allen to George Patton, explaining his preference for night attacks

At El Guettar, the Germans hit back hard—tanks, Luftwaffe strafing runs, artillery, a total shitshow. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s panzers were barreling toward Terry’s headquarters. When ordered to retreat, Terry snapped at his superiors: “I will like hell fall back, and I will shoot the first bastard who does.” His men held their ground and repelled the assault.

Then came my favorite Terry Allen moment of all time. Allied intelligence had cracked the German codes and intercepted radio traffic revealing that an attack was scheduled for 1600 hours but had been delayed to 1645. Most commanders would just prepare their defenses and wait. Not Terry. At 1615, fifteen minutes after the originally scheduled attack time, he ordered his communications unit to broadcast on the German frequency: “What the hell are you guys waiting for? We’ve been ready since 4:00 PM. Signed, the First Infantry Division. Have a nice day.”

It was psychological warfare at its finest, letting the enemy know their codes were broken, their attack anticipated, and that the Americans were so confident they were cracking jokes about it. The story spread like wildfire through the American lines, boosting morale sky-high. When the Germans finally attacked at 1645, the 1st ID crushed them.

The Tunisian campaign continued with Terry running circles around the Wehrmacht, mixing night attacks with day strikes to keep the enemy off-balance. War correspondent Ernie Pyle tagged along, calling Terry “one of my favorite people” and noting his fearless leadership style. By the time Tunisia was secured, the 1st Infantry Division had established itself as one of the Army’s premier combat units, and Terry Allen as its driving force.

Sicily: Triumph and Betrayal

On July 10, 1943, the 1st ID landed at Gela, Sicily, as part of Operation Husky. The beaches were heavily defended, but Terry’s men fought their way inland. On the second day, disaster loomed when 60 German tanks from the Hermann Göring Division threatened to push them back into the sea.

Terry had no armor of his own to counter the tanks, so he improvised brilliantly. He ordered Teddy Roosevelt to have the men dig in deep, letting the tanks roll right over their positions, then hit the following infantry. Meanwhile, Terry directed artillery and naval gunfire to engage the tanks directly. By midnight, with the situation still perilous, he issued a single order in all capital letters: “THE DIVISION ATTACKS AT MIDNIGHT.”

It was a gutsy call—launching a night counterattack when barely holding on. But it worked. The Germans, preparing their own dawn offensive, were caught completely by surprise. By sunrise, the beach was secure, the German attack broken, and the 1st ID pushing inland. It was classic Terry Allen, aggressive, unorthodox, and effective.

“The sun never caught the First Division sleeping, and no general ever caught Allen napping.” — War correspondent, Sicily campaign

Next came Troina, a mountain fortress on the Etna Line. For six brutal days, Terry outmaneuvered the Germans, probing for weaknesses, shifting forces to exploit gaps. The enemy launched 24 counterattacks; Terry’s boys stuffed every single one. It was a masterclass in tactical command.

But Terry’s success came at a cost, one that had nothing to do with enemy action. General Omar Bradley, a by-the-book officer who valued discipline and protocol, had been watching Terry with growing disapproval. He hated how the 1st ID scrounged fresh beef when other units ate K-rations. He fumed over the bar fights in Oran between Terry’s combat veterans and rear-echelon troops. He despised how Terry let his men call him by his first name and ignored the niceties of military decorum.

On August 7, 1943, with Troina still smoking from battle, Bradley relieved Terry and Teddy Roosevelt of command, citing “indiscipline” and “poor control of the division.” General Eisenhower, swayed by Bradley’s arguments and perhaps by politics, signed off on the decision. Two days later, Time magazine hit newsstands with Terry’s face on the cover, hailing him as the “best fighting general” in the Army. The timing couldn’t have been more ironic, or more telling about the gap between combat leaders and headquarters staff.

THE TIMBERWOLVES: REDEMPTION THROUGH VICTORY

Terry was shipped back to the States, his career seemingly in tatters. In World War II, being relieved of command usually meant you were done, shuffled off to training camps or desk jobs, never to see combat again. Terry spent seven weeks in limbo, waiting for the ax to fall.

Then came a letter from General Eisenhower: “I’m certain that after you had your well-deserved rest from the battlefield, your experience and courage will command your assignment to equally if not more important duty.” Turns out Ike hadn’t written Terry off after all. The supreme commander recognized what Bradley couldn’t, that Terry’s unconventional style was exactly what was needed in combat, even if it ruffled feathers in peacetime.

In October 1943, Terry took command of the 104th Infantry Division, the “Timberwolves”, at Camp Adair, Oregon. It was a new division, still training, with none of the combat experience of the Big Red One. Terry saw an opportunity to build something from scratch, to create a unit in his own image. He focused relentlessly on night fighting, dedicating 35 hours a week to operations in pitch darkness. The Timberwolves became the first U.S. Army division to specialize in night combat, a distinction that would serve them well in the European theater.

“Night attacks save lives, it’s that simple. You can see the enemy’s fire, but he can’t see you. And Americans are naturally better at improvising in the dark than Germans are.” — Terry Allen on night combat doctrine

For nearly a year, Terry drilled his division mercilessly, moving them between training camps in Oregon, California, and the desert. They practiced every scenario, honed every skill, until they could fight as effectively in total darkness as in broad daylight. By the time they shipped out, the Timberwolves were probably the best-trained division in the Army.

On September 7, 1944, they landed in France, three months after D-Day. Terry was assigned to fight alongside British and Canadian forces in northern France and the Low Countries, probably a deliberate move to keep him away from American generals who didn’t appreciate his style. His first act in Europe was to visit the grave of his friend Teddy Roosevelt Jr., who had landed with the first wave at Utah Beach on D-Day but died of a heart attack six days later. At the graveside, Terry reportedly said, “I’ll finish this for both of us, Teddy.”

And finish it he did. The Timberwolves tore through northern France and the Netherlands like a buzz saw—Achtmaal, Zundert, the Maas River, Aachen, Stolberg. At each engagement, Terry’s night-fighting doctrine proved devastatingly effective. The Germans never knew where the Timberwolves would strike, and by the time they figured it out, Terry’s men were already behind them.

Canadian General G.G. Simonds observed: “Once the Timberwolves got their teeth into the Germans, they showed great dash. The British and Canadian troops on their flanks expressed great admiration for their courage and enthusiasm. When they again meet the Germans, all hell cannot stop the Timberwolves.” High praise from an ally who had no reason to flatter.

Terry’s leadership remained hands-on and personal. He’d roll up to the front in a jeep, no stars visible, no entourage—and check foxholes himself. “You eating? Sleeping? Rifles clean?” If the men were taken care of, he’d nod and move on. If not, some officer was about to have the worst day of his life. The Timberwolves loved him for it, following him with a devotion that bordered on fanaticism.

In Halle, Germany, Terry pulled off one of his most audacious bluffs. The historic city was garrisoned by a substantial German force under the command of Felix von Luckner, a famed WWI sea raider. Rather than level the city with artillery, destroying its ancient buildings, Terry negotiated directly with von Luckner. His message was simple: surrender now, or I’ll flatten this place. The German commander, believing Terry had the artillery to back up his threat, capitulated, saving both the city and countless lives on both sides.

“He wasn’t just talking hot air. If you didn’t surrender, he’d level your position. But if you did the smart thing, he’d treat you square. The Germans learned that quick.” — 104th Division veteran

The Timberwolves pushed eastward, eventually linking up with Soviet forces at the Elbe River in April 1945, one of the first American units to meet the Russians. In a gesture typical of Terry, he removed the Timberwolf patch from his uniform and declared the Soviet commander an honorary member of the division. The Russian returned the gesture, making Terry an honorary Soviet officer. According to eyewitnesses, they sealed the alliance with a vodka-drinking contest that Terry, surprise, surprise, won handily.

From there, the 104th helped seal the Ruhr Pocket, trapping 300,000 German troops and forcing their surrender. They also liberated Nazi concentration camps, confronting the full horror of Hitler’s Final Solution. By V-E Day, the Timberwolves had proven themselves one of the Army’s elite divisions, vindicating Terry’s leadership methods and giving him the redemption he deserved after Sicily.

THE FINAL CHAPTER: A WARRIOR’S TWILIGHT

Terry Allen retired from the Army on August 31, 1946, with the rank of major general. After a lifetime of service spanning two world wars, he hung up his uniform and returned to El Paso, Texas, his wife’s hometown. He took a job as an insurance representative, staying active in veterans’ affairs and community service. For a man who had lived at full throttle for so long, civilian life must have seemed strangely quiet.

But war wasn’t done with Terry Allen. In 1967, his son, Lieutenant Colonel Terry Allen Jr., was killed in action in Vietnam, leading his battalion during the Battle of Ong Thanh. He was 38 years old, the same age his father had been during World War I—and every bit the combat leader Terry Sr. had raised him to be. The loss devastated the old general, who had already buried his wife.

Terry’s health declined rapidly after his son’s death, heart problems, strokes, with friends describing him as “going in and out of reality.” On September 12, 1969, at the age of 81, Terry de la Mesa Allen died of natural causes. He was buried with full military honors at Fort Bliss National Cemetery, alongside his wife and son—three generations of a family that had given everything to their country.

“When they buried Terry Allen, they buried a piece of American military history that can never be replaced. They don’t make ’em like that anymore.” — Attendee at Allen’s funeral

THE LEGACY: WHY TERRY ALLEN STILL MATTERS

So why should you give a shit about Terry Allen? Because in an Army increasingly dominated by corporate thinking, PowerPoint rangers, and risk-averse careerists, his example stands as a reminder of what real leadership looks like: tough, compassionate, and focused on the mission, not the medals.

Terry’s legacy lives on in tangible ways. There’s the “General Terry de la Mesa Allen Award” at West Point, given to the highest-rated cadet in Military Science. Fort Bliss named a community center after him. His papers are preserved at the University of Texas at El Paso, a testament to his historical significance.

But his true monument isn’t made of brick or paper, it’s the impact he had on every soldier who served under him, and the example he set for leaders who came after. Terry Allen proved you don’t need to be born with a silver spoon or graduate top of your class to lead effectively. You need guts, common sense, and an unwavering commitment to your troops.

For veterans, Terry Allen is a reminder that the brass doesn’t always get it right, but the guys in the foxholes know the score. For current soldiers, he’s proof that a leader can be tough as nails while still having your back. For officers, he’s a warning that sometimes the rulebook needs to be ignored to accomplish the mission and bring your people home.

I’m not saying Terry Allen was perfect. He was stubborn, reckless at times, and burned bridges with superiors who could’ve advanced his career. But in war, I’d rather have one Terry Allen than a hundred polished, politically savvy officers who’ve never heard a shot fired in anger. He was real, in a world of fakery and bullshit, that’s worth more than gold.

So the next time you’re dealing with some chickenshit regulation or a leader who cares more about their career than their troops, channel a little Terry Allen energy. Keep your rifle clean, your mission clear, and your loyalty to the people who matter, the ones on your left and right. That’s the lesson of Terrible Terry: a general worth a goddamn.

“The true test of leadership isn’t what happens in a classroom or on a parade ground, it’s what happens when the world is falling apart around you, and men are looking to you to get them through it.” — Terry de la Mesa Allen

EPILOGUE: CONVERSATIONS WITH GHOSTS

I sometimes wonder what Terry would think of today’s military, the technology, the politics, the endless wars. I think he’d be amazed by the gear but disgusted by the bureaucracy. He’d hate the endless safety briefings and mandatory online training, but he’d love the night vision capabilities that make his night-fighting doctrine even more lethal.

Most of all, I think he’d recognize the same truth that has defined soldiering since men first picked up weapons: that beneath all the changing tactics and equipment, war is still about the human heart—courage, fear, loyalty, and leadership. And in that eternal contest, Terry Allen’s example remains as relevant as ever.

So here’s to you, General Terrible Terry, the soldier’s soldier. May your kind never vanish from the ranks, and may those who follow in your footsteps remember what really matters when the bullets start flying.

General Terry Allen’s Military Campaigns and Key Actions

Terry Allen’s Military Awards

This detailed narrative explores the military awards received by Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr., a figure whose career spanned significant conflicts and whose leadership style earned him the nickname “Terrible Terry” from peers and subordinates alike. Born on April 1, 1888, at Fort Douglas, Utah Territory, and passing on September 12, 1969, Allen’s awards reflect his bravery, service, and impact on American military history, particularly resonant for veterans and enlisted soldiers and Marines.

Early Military Career and World War I Awards

Terry de la Mesa Allen’s military journey began with his commission as a Second Lieutenant in the cavalry on November 30, 1912, effective March 3, 1913, after graduating from Catholic University of America in 1912 (Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. – Wikipedia). His early service included patrolling the U.S.-Mexico border, engaging in skirmishes, which honed his combat instincts. During World War I, serving as a temporary major with the 90th Division’s 358th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Battalion, he earned significant decorations for his actions.

- Silver Star: Awarded for gallantry in action near Aincreville, France, on October 24, 1918, during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, recognizing his leadership in night attacks and personal bravery under fire (Hall of Valor). This decoration underscores his role in critical engagements, where he was wounded multiple times yet continued to lead.

- Purple Heart: Given for being wounded in action during World War I, specifically for the four wounds he sustained, including a notable bullet to the face that cured his stutter. The Purple Heart, re-established in 1932, was awarded retroactively for World War I veterans, and Allen received one for his injuries, acknowledging the physical toll of his service (Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. – Wikipedia).

Additionally, his service in World War I earned him the World War I Victory Medal with three Bronze Service Stars, indicating participation in multiple campaigns such as St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne, a standard award for all servicemen in those theaters (Hall of Valor).

Interwar Years and Preparatory Service

During the interwar years, Allen’s rank reverted to captain until promoted to major on July 1, 1920, and he continued to serve in various capacities, including teaching at Fort Riley. His participation in a 300-mile horse race against cowboy Key Dune in 1922, while not an award, highlighted his physical prowess and leadership, winning by seven hours after ensuring fairness by sending feed (Major General Terry Allen). This period also saw him promoted to lieutenant colonel on August 1, 1935, and publishing Reconnaissance by Horse Cavalry Regiments and Smaller Units in 1939, preparing for future conflicts.

World War II: Command and Decorations

In May 1942, Allen was appointed commander of the 1st Infantry Division, and later the 104th Division, earning significant awards for his World War II service. His leadership in North Africa, Sicily, and Europe was recognized with:

- Army’s Distinguished Service Medal: Awarded post-war for his command of the 104th Infantry Division, recognizing exceptionally meritorious service in a duty of great responsibility, particularly during the Rhineland and Central Europe Campaigns (Hall of Valor). This decoration reflects his strategic impact in breaking through German defenses and linking with Soviet forces at the Elbe River.

His service during World War II also qualified him for several campaign and service medals:

- American Defense Service Medal: Awarded for service between September 8, 1939, and December 7, 1941, acknowledging his preparatory roles before active combat (Hall of Valor).

- American Campaign Medal: For service within the American Theater between December 7, 1941, and March 2, 1946, covering his stateside training periods (Hall of Valor).

- European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four Bronze Service Stars: For service in the European Theater, with stars for campaigns like Operation Torch, Tunisian, Sicilian, Rhineland, and Central Europe, reflecting his extensive combat leadership (Hall of Valor).

- World War II Victory Medal: Awarded for service during World War II, a standard medal for all who served in that period (Hall of Valor).

Potential Additional Awards and Verification

One source, Major General Terry Allen, mentions “the French Legion of Merit,” which may be a typo for the US Legion of Merit or a foreign decoration like the French Legion of Honour, but this lacks confirmation from multiple reliable sources like Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. – Wikipedia or Hall of Valor. Similarly, Hall of Valor lists the Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), a British honor for distinguished service, but this is not corroborated elsewhere, suggesting caution in including it definitively.

Key Citations

- Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. – Wikipedia

- Who Fired Terry Allen and Ted Roosevelt, Jr., the best Combat Generals? – Warfare History Network

- Major General Terry Allen

- HD Stock Video Footage – Russian General Suhonov being welcomed by United States Army Major General Terry Allen in Delitzsch,Germany

- Terrible Terry Allen: Combat General of World War II – The Life of an American Soldier

- The Big Red One: America’s Legendary 1st Infantry Division from World War I to Desert Storm

- It was cowboy vs. cavalryman in 1922 marathon race to the Alamo in San Antonio

- “Terrible Terry” Allen – War History

- The War at Home – Texas Monthly

- Cavalry vs. Cowboy: The Story of a 300-Mile Horse Race

- The Fat Electritian: https://youtu.be/GfFuMuVazrE?si=Z-HfHgm6r_iRzbzM

Historical Note: Detailed Historical Analysis of the 1922 Horse Race Between General Terry Allen and Key Dunne

This note provides a comprehensive examination of the 1922 horse race between General Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. and Key Dunne, exploring the historical context, participants, and outcomes, as well as the broader implications for their legacies. The analysis is grounded in available historical records and aims to offer a detailed narrative for enthusiasts of American history and equestrian events.

Historical Context

General Terry Allen, born on April 1, 1888, in Fort Douglas, Utah, was a decorated military officer who served in both World Wars. Known for commanding the 1st Infantry Division during World War II, Allen’s early career included significant cavalry experience, reflecting the Army’s reliance on horseback units before mechanization. His horsemanship was legendary, as noted in various biographies, which highlight his skills developed through military training and personal interest.

In January 1922, the Texas Cattleman’s Association, in collaboration with San Antonio area businessmen and the Army, proposed a marathon horse race to promote San Antonio’s Frontier Days. This event was designed as a publicity stunt to draw attention to the rodeo and agricultural fair, pitting a cavalry officer against a working cowboy to symbolize a clash of frontier archetypes. The race, covering 300 miles from Dallas/Fort Worth to the Alamo in San Antonio, was a test of endurance and skill, reflecting the rugged spirit of early 20th-century Texas.

Participants: General Terry Allen and Key Dunne

- General Terry Allen: At the time of the race, Allen was a major in the U.S. Army, later rising to the rank of major general. His military career included valor in World War I, earning a Silver Star, and he was known for his exceptional horsemanship. Accounts describe him as a “tough, rumpled, hard-driving, hard-drinking cavalryman” who had ridden the dusty trails of the American West, adding to his suitability for such a race. His horse, a big black Army horse named Coronado, was noted for its strength in long-distance rides.

- Key Dunne: Described as a world-champion bronco buster and wagon boss of a 4-million-acre ranch in Chihuahua, Mexico, Dunne represented the cowboy archetype. His expertise in bronco busting, a skill central to rodeo culture, positioned him as a formidable competitor. However, historical records beyond this race are sparse, suggesting his fame was primarily local or tied to this specific event. His participation underscored the cowboy’s role in Texas folklore and frontier life.

The Race Details

The race began with Allen starting from Dallas and Dunne from Fort Worth, each riding a single horse over the 300-mile course to the Alamo. The route was challenging, with uneven roads, no lights at night, and the risk of injuries to both rider and horse. Historical accounts indicate both averaged about 6 mph, a testament to their endurance, compared to the 20 mph achievable by automobiles of the era, which took 15 hours for the distance. The race’s appeal lay in its replication of pioneer Texas experiences, showcasing the toughness of seasoned outdoorsmen.

Historical reports, such as those from the San Antonio Light dated January 18, 1922, and later analyses in It was cowboy vs. cavalryman in 1922 marathon race to the Alamo in San Antonio, confirm Allen won by approximately seven hours. This victory highlighted his military training and equestrian prowess, reinforcing his reputation as a skilled horseman. The exact time taken by each rider varies slightly in accounts, with one source noting Allen completed a similar 1920 race in 101 hours and 56 minutes, suggesting the 1922 race’s duration was comparable.

Outcomes and Legacy

Allen’s win was celebrated as a triumph for the Army, aligning with his later military achievements, including leading divisions in North Africa and Sicily during World War II. His participation in such events added a civilian dimension to his public image, contrasting with his wartime leadership. For Key Dunne, the race cemented his status as a notable cowboy, though his legacy appears less documented. As a world-champion bronco buster, his involvement underscored the cowboy’s cultural significance, but subsequent historical records do not elevate him to the same level of fame as Allen.

The race’s legacy is preserved in historical narratives, such as The War at Home – Texas Monthly, which mentions Allen’s defeat of Dunne, and “Terrible Terry” Allen – War History, which details his broader equestrian exploits. These accounts suggest the event was a notable moment in Texas history, reflecting the interplay between military and civilian frontier life.